The Heroes of Fawcett Comics

An Oral History of Captain Marvel (3/12)

The Fawcett Years, part 3

By Zack Smith • 27 December 2010

The Fawcett Years: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 The Lost Years: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 The Shazam! Years: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 • New Beginning Modern Years The Future

© Zack Smith; originally published by Newsarama

The End of Fawcett Comics

Merchandising

With Captain Marvel Jr. and Mary Marvel at his side, Captain Marvel was the king of super-hero comics in the 1940s. There was even a bevy of Captain Marvel merchandise, much of it sold directly through Fawcett Comics itself.

Chip Kidd (author, Shazam!: The Golden Age of the World’s Mightiest Mortal):

“One interesting thing Michael Uslan brought up at our SDCC panel is that most of the memorabilia we depict in our book is one-of-a-kind — either prototypes for things that didn’t get made, or things that got made, but only one or two examples are known to exist.

“This surprised me, given how popular the character was. But Uslan explained to me that as the lawsuit went on longer and longer, more of these manufacturers got scared, and perhaps didn’t know about the details until they tried announcing the material in a trade magazine, and DC sent them a cease and desist order.”

Marvel Family Villains

In their comics, the Marvel Family battled a wide variety of foes — Jr. and Mary had Sivana’s equally evil children Sivana Jr. and Georgia Siviana to contend with, occasionally teamed with the not-so-good doctor as the “Sivana Family.”

There was Ibac, a wimp named Stinky Printwhistle granted Marvel-smashing strength by the devil himself, gaining the power of Ivan the Terrible, Ceseare Borgia, Attila the Hun and Caligula (Captain Marvel Adventures #8, 1942). Lord only knows what a more literal interpretation of those abilities would result in today… DC editors, please don’t get any ideas.

Captain Marvel Jr. had the similar Sabbac, who… oh, let’s not get hung up on acronyms (Captain Marvel Jr. #4 (Feb. 1943). There was even an evil counterpart to Uncle Dudley in Aunt Minerva, an elderly female gangster determined to make Captain Marvel her latest husband.

Ironically, one of the most memorable Marvel foes only appeared in one story. In The Marvel Family #1 (Dec. 1945), the trio was pitted against the wizard Shazam’s previous champion, Teth-Adam, aka “Mighty Adam,” who had abused his powers and been banished to a distant star. 5,000 years later, the renamed “Black Adam” returned for revenge before being tricked into saying “Shazam” by Uncle Dudley and reduced to dust. A few decades later, he got better.

Many of the Marvel foes gathered together in the best-remembered Golden Age storyline, “The Monster Society of Evil!” Inspired by the format of the serial, it appeared in installments stretched across 25 issues of Captain Marvel Adventures #23-46 (1943–45).

In it, Captain Marvel battled a massive gathering of foes (including Hitler, Stalin and Tojo) brought together by a disembodied voice called “Mr. Mind.” Several chapters in, it was revealed Mr. Mind was actually an adorable green alien worm with glasses and a radio around his neck to broadcast his thoughts. After many battles, the World’s Wickedest Worm was finally captured, convicted of 186,744 murders, executed and stuffed. Like Black Adam, he got better.

“The Monster Society of Evil” helped kick off many ideas still seen in super-hero comics today — the epic-length crossover, the cosmic threat, the villains allied against the hero. But though it received a small-press reprinting in the early 1990s, a planned reprint from DC has been indefinitely delayed.

It’s easy to see why. Though the story still has energy and charm, one problem of the early Captain Marvel stories is that they reflected an exaggerated version of the real world, which also meant real-world stereotypes.

With characters such as Billy’s wide-eyed, big-lipped black friend “Steamboat” and the buck-toothed Japanese villain “Nippo from Nagasaki” (to name just a few), what came off as fun and exciting in the 1940s comes off today as, well “racist as hell”…

Mike Kunkel (writer/artist, Billy Batson and the Magic of Shazam):

“There are things in the original stories that you just don’t want to approach as a creator.”

Jeff Smith (writer/artist, Shazam!: The Monster Society of Evil):

“The black characters are depicted in a very stereotypical manner, which was sadly typical of the time, and so were the Japanese characters — which, again, was typical in WWII.

“I don’t see why they don’t reprint it. I hope they do reprint it, and say, ‘This is what was done at the time, and it’s pretty bad, but it’s also part of the story.’”

Chip Kidd:

Chip Kidd:

“We talked about that at the San Diego Comic-Con panel. Monster Society of Evil came up, and we found out it was on 'permanent hold' for this reason, the characterization of certain racial stereotypes at the time.

“One thing Michael Uslan pointed out is that it’s about putting it in historical perspective. This really was an attitude that was widely held at the time, even if it wasn’t right. And to deny the publication of something that was not intended to be racist, basically, is to deny an audience some really terrific work.

“One thing I included in my book was a series of guidelines that Fawcett sent to their writers and artists in the 1940s which regarded eliminating racial stereotypes, indicating that ethnic groups were not to be not to be ‘ridiculed or intolerated.’ So they eventually did away with that.”

The whole Monster Society storyline was reprinted in the early 1990s, and can go for several hundred dollars on eBay.

Jeff Smith:

“That was part of my business expenses for doing my Monster Society story. I think I paid three or four hundred bucks for it in 2006. But it’s a pretty fun read! Parts of it are pretty corny and don’t work at all for modern eyes. But some of it’s very fun and over-the-top, and there’s an amazing amount of ways for them to get a gag over Billy’s mouth so he can’t say ‘Shazam!’

“There’s just also some things that are… not acceptable today. It was just ignorance and lack of knowledge of other people.”

Mark Waid (Kingdom Come, other Captain Marvel stories):

“Oh, it is racist as hell! But speaking ex parte, as an outside observer without any sort of especial inside knowledge, my understanding was the timing was not right — under different circumstances, in a different time, DC would have reprinted that with disclaimers that it was a product of its time and contained racially-insensitive elements.

“But I can understand as why, as you were suddenly going from the Paul Levitz regime to a new regime with a new boss who has a new boss themselves, and DC’s whole place in the Warner corporate structure is up in the air, I can understand why that might not be the best time to reprint ‘The Monster Society of Evil.’

“I hope that that doesn’t mean that it will never reprinted, but I will say it should have been reprinted in a nice, cheap, affordable reprint. But that’s a very tough call for a company to make. I’m not taking anybody’s side — it’s easy to sit on the sideline and say ‘Reprint it!’, but you try doing that when you don’t even know who your new boss is. Maybe you should at least get the lay of the land before you reprint this thing.”

Alex Ross (Kingdom Come, Shazam: Power of Hope, Justice):

“I don’t think you should bury the past, and I’d rather see a full historical document, provided with a context to explain these depictions. I really can’t imagine these stereotypes hold up much worse than the often-reprinted Spirit stories that Will Eisner did with Spirit’s sidekick, Ebony.”

Mike Kunkel:

“It’s very hard, because you’re judging a past with different values. From today’s standards, you’d say ‘I’d never draw that,’ or ‘I’d never write that.’ You see it today and go ‘Geeeeezzzz.”’

Jeff Smith:

“But it’s an important story in comics history, because it was the first long-form comic. It’s the ancestor of today’s graphic novels — a long story that continued for almost two years in every issue of Captain Marvel, with a beginning, a middle and an end, where they capture Mr. Mind.

“My Monster Society was actually only the first half of the story. I keep threatening to come back and do the story where they chase Mr. Mind around the world to finally catch him. I haven’t got any plans to do it just yet, but I’ll keep threatening. (laughs)”

By the early 1950s, super-heroes were on their way out, giving way to such new genres as romance and horror comics. Captain Marvel and his family soldiered on, but the format of their books was already starting to come off as dated and repetitive.

Chip Kidd:

“In a lot of ways, they painted themselves into a corner a bit, because how many ways can you think of to keep Billy from saying the word? Of course, you’re limited by your imagination, but still, there’s only so many ways to keep him from doing that.”

Michael Uslan (Executive Producer of all Batman movies):

“The comics industry was going into the closest damn thing to a depression — you could call it a recession easily — after WWII. The core need for super-heroes was gone after WWII, and new genres were arising. Of course, the biggest new ones were horror and crime comics.

“Every publisher, in order to stay alive, tried to turn their comics into horror or crime comics, whether it was turning Captain America into Captain America’s Weird Tales or Black Cat into Black Cat Mystic.

“And Captain Marvel was not without its run of turning into horror comics, much to the chagrin of Beck and Binder. They were being ordered to do this, and C.C. told me, ‘At that point, Captain Marvel should have died. The book had lost its innocence, it had lost its way.’ He was very resentful of this, of it being made to conform to the market.”

Captain Marvel found himself fighting foes that had a darker edge than the likes of Sivana and Mr. Mind. King Kull the Beast Man was a horror-influenced ruler of a dead race of “Submen” who battled Captain Marvel with a combination of brute strength and super-science. Even deadlier was Mister Atom, a robot powered by atomic energy (Captain Marvel Adventures #78 (Nov. 1947).

The Final Days of Fawcett Comics

But with sales declining, there was one foe Captain Marvel couldn’t defeat — litigation.

DC posted multiple lawsuits against Fawcett — in one case, a judge’s decision that Captain Marvel did not infringe upon Superman was overturned by another judge, who just happened to be the first judge’s brother.

Manley Wade Wellman, an acclaimed author who would go on to win Edgar and World Fantasy Award for such works as his “John the Balladeer” stories, had helped write some of the original Captain Marvel stories. According to biographers, Wellman hurt Fawcett’s case by testifying that they had been instructed to copy Superman.

When asked how he could prove he had worked on the books, as writers weren’t directly credited, Wellman showed how he had incorporated his initials into word balloons in the pages of Captain Marvel stories. It was one of many blows to Fawcett from DC, who went out of their way to prove the World’s Mightiest Mortal was just a shadow of the Man of Steel.

At this point, comic sales were down and a decision in DC’s favor could put Fawcett out of business. Tired of battling DC in court for years, Fawcett agreed to settle with the company and stop publishing the Captain Marvel books. The terms of the settlement prevented them from resuming publication without DC’s permission — something the company was unlikely to give.

Michael Uslan:

“Fawcett was hog-tied after that settlement. They couldn’t allow Captain Marvel to show his face ever again, or the settlement could become very unsettled.”

Alex Ross:

“Captain Marvel was magic based, and that should have been enough to keep Fawcett removed from the science fiction-derived Superman, especially when a flood of costumed imitators that DC didn’t sue got away red-handed.

“Ultimately the folks at Fawcett did their jobs too well, and if not for their success at beating Superman at his own game, the continued lawsuits would have ceased. It’s a bitter irony that DC now owns him. It’s even more ironic that Marvel Comics undercuts anything DC does with him by taking the name early on.”

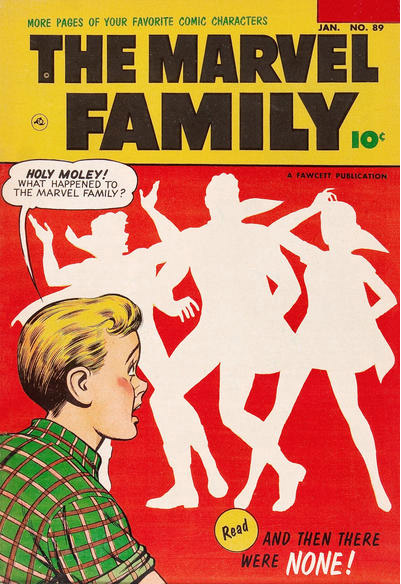

The last issue of a Captain Marvel comic was The Marvel Family #89 (Jan. 1954). The cover story, entitled “And Then There Were None!” showed a boy gaping at the empty silhouettes of Captain Marvel, Captain Marvel Jr. and Mary Marvel. “Holy Moley!” he extolled. “What happened to the Marvel Family?”

In the story, the Marvels turned up okay. For readers, it would be nearly two decades until they saw their heroes again.

Chip Kidd:

“It’s very hard to understand and fathom the impact these books had. And ultimately, Captain Marvel was a victim of his own success.”