The Heroes of Fawcett Comics

An Oral History of Captain Marvel (5/12)

The Lost Years, part 2

By Zack Smith • December 29, 2010

The Fawcett Years: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 The Lost Years: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 The Shazam! Years: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 • New Beginning Modern Years The Future

© Zack Smith; originally published by Newsarama

Here we look at the other characters who tried to take Captain Marvel's place. We also take a look at the role Captain Marvel had in shaping the popular culture of the 1960s, in ways you might not have imagined.

Special thanks to Michael Uslan, who shares more anecdotes in his autobiography, The Boy Who Loved Batman (Red Lightning Books, 2011).

Meet the Pretenders

As time marched on, super-heroes began to make a comeback. DC Comics found success with new versions of the 1940s characters the Flash and Green Lantern, who were later teamed with a number of veteran heroes as the Justice League of America. Publisher Marvel Comics, wanting to imitate this success, ordered writer Stan Lee to come up with a super-team for their company.

The result was Lee and Jack Kirby’s The Fantastic Four. And nothing was ever the same.

Lee, in collaboration with Kirby and other artists such as Steve Ditko, Wally Wood and Gene Colan, turned out a slew of characters whose names you all know — the Amazing Spider-Man, the Incredible Hulk, the Mighty Thor, the Uncanny X-Men, Doctor Strange, Daredevil, the Silver Surfer — characters for whom soap-opera plotlines, intense self-loathing and mind-boggling cosmic concepts were as much a part of them as colorful costumes and slam-bang action.

By the mid-1960s, Marvel’s success, combined with the campy TV series Batman with Adam West, had revitalized super-heroes. Many characters from the Golden Age were revived… but due to Fawcett’s settlement with DC, Captain Marvel couldn’t be one of them.

In 1965, award-winning cartoonist Jules Feiffer wrote The Great Comic Book Heroes, a seminal combination of essay and reprints about the characters of the 1940s. The book revitalized interest in many of these characters, but DC would only allow one page of Captain Marvel comics to be reprinted, his origin.

Michael Uslan (Executive Producer of all Batman movies):

“That book was essential. That was the only thing we had that gave us clues about the Golden Age of Comics. It was our Bible. It was my first exposure to characters like the Spectre, whom I had to pester Julie Schwartz to bring back.

“He wrote me back and said, ‘We can’t! The Comics Code says no walking dead!’ So I wrote him a note back that said, ‘Yeah? Really? What about Casper?’

“The next thing I know, I got a note back from Julie saying, ‘You’ll be happy to know that the Spectre is coming back in Showcase #60, teamed up with Doctor Mid-Nite.’ And he did come back in that issue, though not with Dr. Mid-Nite. And that remains one of the proudest moments of my comic-collecting life, though it wouldn’t have happened without Feiffer’s book. That was essential.”

Even with legal issues preventing his comeback, Captain Marvel remained a powerful force in popular culture. On the TV series Gomer Pyle, USMC, the title character co-opted Captain Marvel’s cry of “Shazam!” as his own catchphrase. The Beatles referenced Captain Marvel in their song “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill” on 1968’s The White Album.

And Captain Marvel Jr. may have had the greatest pop-cultural influence of all — in the preserved apartment of Elvis Presley’s family in Memphis, Tennessee, a copy of Captain Marvel Jr. sits on Elvis’ desk. Bobby Smith, cousin to the King, credited the rock legend’s hairstyle and one-piece jumpsuits to The Most Powerful Boy in the World.

Fatman, The Human Flying Saucer

As the 1960s wore on, the good Captain saw not one, not two, but… well, two-and-a-half revivals by his creators. C.C. Beck was lured back into comics for Fatman, The Human Flying Saucer, which reunited him with Otto Binder as a writer. The book was published by “Lightning Comics,” a division of Milson Publishing.

Beck intensely disliked the new direction of comics, and later complained in an interview that one of Binder’s scripts opened with the explanation that the story would mostly consist of quippy dialogue with little plot, as was the apparent trend those days. Perhaps this distaste for modern heroes was reflected in a cover that saw Fatman fighting a group of villains billed as “The Awesome Foursome.”

Roy Thomas:

“C.C. Beck was a little thornier than Otto Binder. I admired Beck greatly, but he started publishing things that were constantly berating what Marvel and especially DC were doing. He had the right to do this, but I often disagreed with him.

“At one point, we were exchanging letters back and forth, and he proposed that we publish these letters, to boost both of our profiles, to arouse some interest and I told him that I didn’t really care to around interest by creating the idea that we were having a feud based on a personal exchange of letters.

“I just looked at him as someone who was a good artist, and had some opinions that just didn’t make any sense to me, and an attitude that didn’t make any sense to me. While we got along well on a couple of times we met in public, such as the San Diego convention in 1977, we never really had that much to say to each other later.

“I remember I met him at that convention with my wife Dann. He was playing the banjo and talking to people, and he was on a panel, and afterward, Dann came out and told me he was the only negative person on the panel, and one of the bitterest people she’d ever seen.”

Combining the whimsy of the Captain Marvel tales with the campy attitude of many 1960s heroes, Fatman: The Human Flying Saucer’s tale of a obese young millionaire given the ability to turn into, well, a flying saucer lasted for only three oversized issues. “Holy strawberry shortcake!” just didn’t have the same ring as Captain Marvel’s “Holy moley!”

Michael Uslan:

“I read it because at the time I was in communication with Will Lieberson, who was actively involved in that venture with C.C. and Otto. When I saw Fatman and the costume and the cape and that Binder and Beck were working on it, I had such high hopes. And then I read it and wasn’t impressed with it at all.

“It was a one-joke concept that wore very, very thin very, very quickly. I thought Otto did a better job with the character in the form of Bouncing Boy of the Legion of Super-Heroes than he did with Fatman.

“I’d also say you’d have to go back to Siegel and Shuster’s Funnyman [their unsuccessful post-Superman character, and comics’ first Jewish super-hero] to find something to equate to the failure of Fatman.”

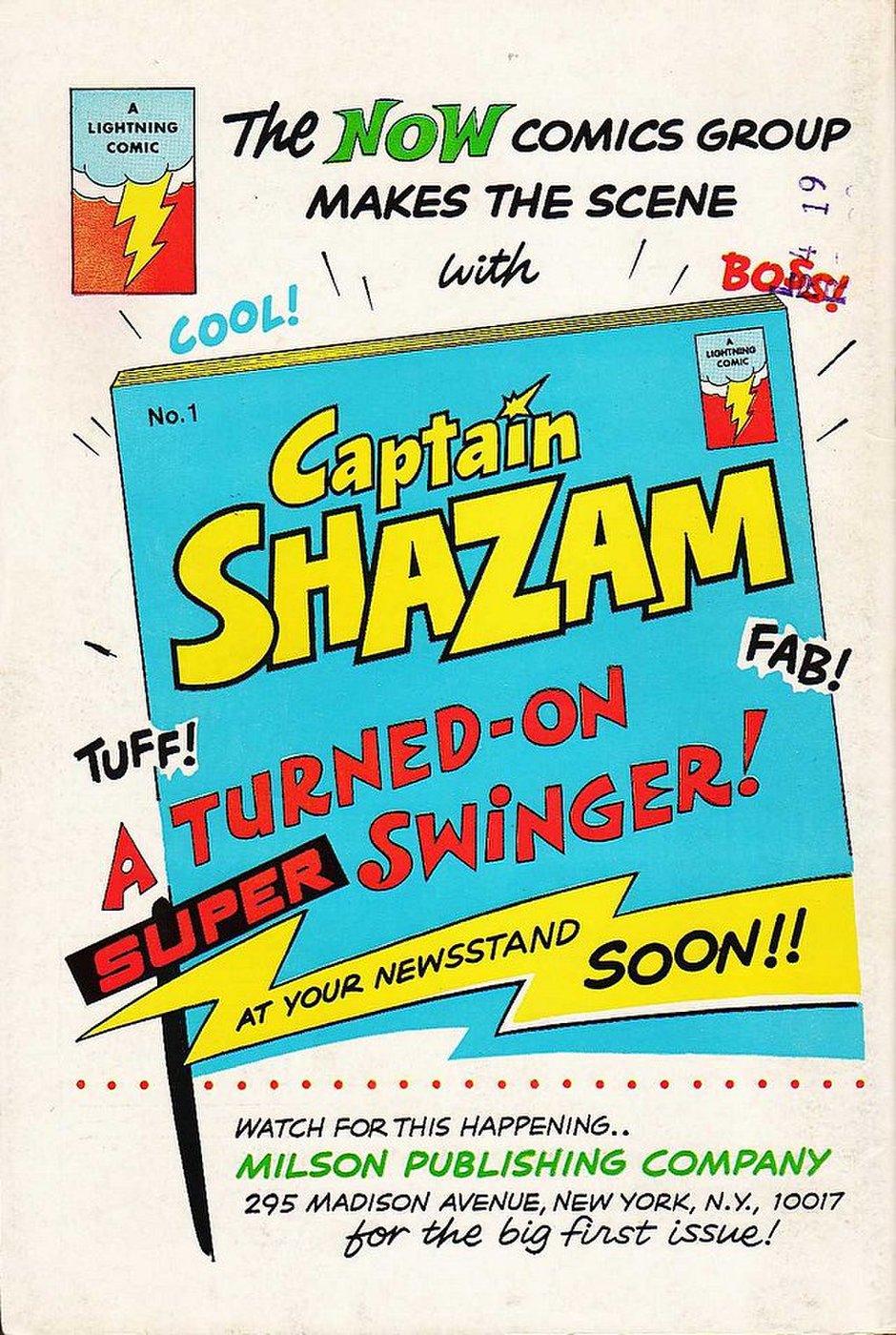

Captain Shazam

Another Beck/Binder Lightning Comics collaboration was advertised, but never got off the ground (the “half” we were talking about). “Captain Shazam,” according to reports, would have been a variation on Bill Parker’s original conception for Captain Thunder, in that six agents (whose last initials spelled “SHAZAM”) would be killed, only to have their abilities combined into a seventh agent.

No actual art exists for the character billed as a “turned-on super-swinger,” though at least readers were spared more potentially horrific unintentional entendres.

Michael Uslan:

“I remember being up in Lieberson’s office, and corresponding with both Otto and C.C. about Fatman and Captain Shazam. Captain Shazam was never more than an advertisement — the company went under before they could publish an issue. I always had it in my youthful mind that this would be the thinly-disguised return of Captain Marvel, the same way I was disappointed that Fatman wasn’t.”

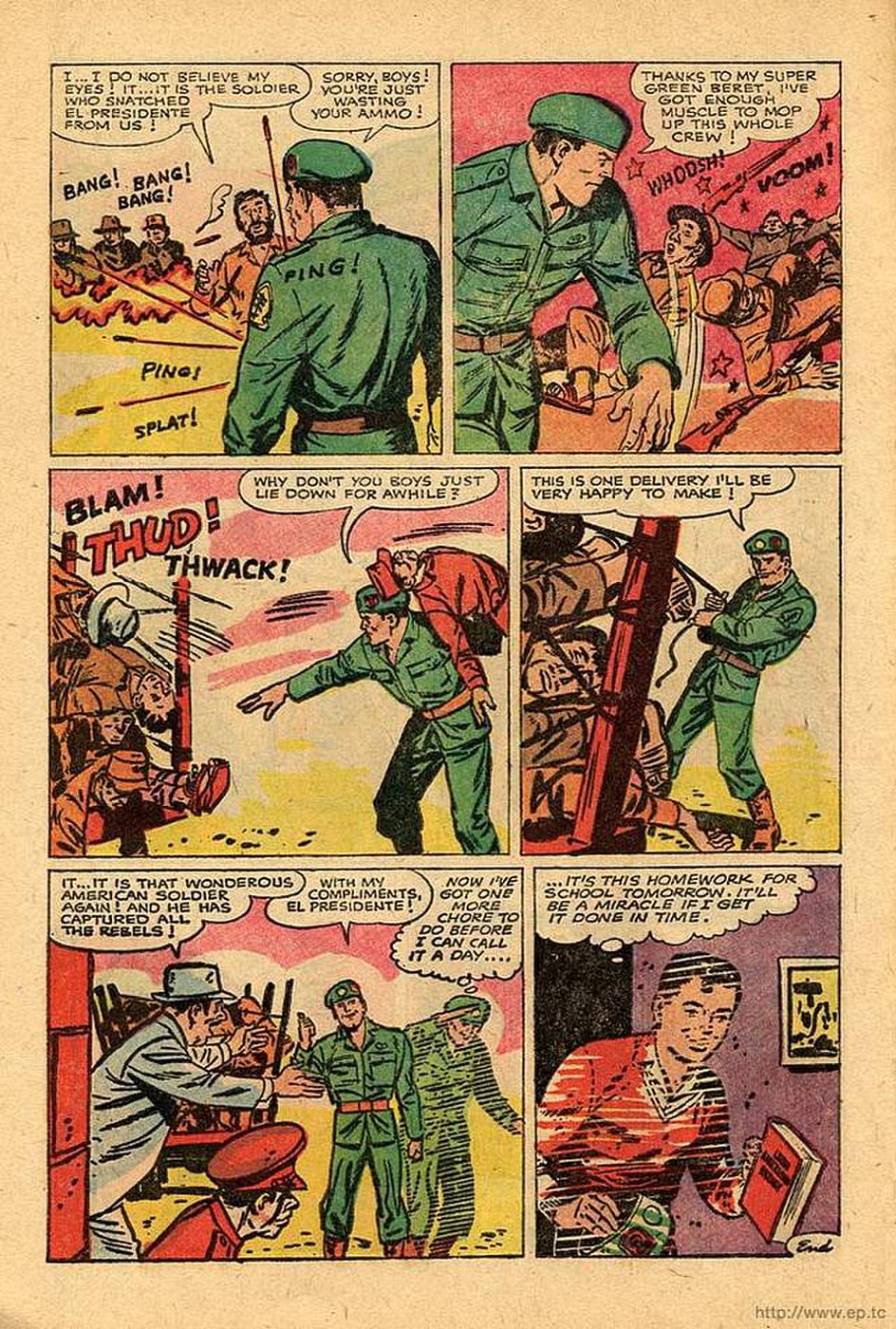

Super Green Beret

On his own, Otto Binder made one more stab at a Captain Marvel-esque character from Lightning Comics with Tod Holton, Super Green Beret. Lasting two oversized issues, it told of a young boy given a magic beret by his soldier uncle, which let him transform into a super-powered adult soldier who could travel through space and time to battle communists, Hitler, and more.

Prone to such declarations as “Doing homework requires a lot of energy — not to mention fighting the Viet Cong!”, Tod’s adventures didn’t last long, though you can read them online here.

Michael Uslan:

“Let’s go to the context of the time. At that time, there was that huge number-one song ‘Ballad of the Green Berets.’ There was The Green Berets movie with John Wayne and David Janssen. There was the Tales of the Green Berets newspaper strip. And most importantly, there was the number-one bestseller The Green Berets.

“’The Green Berets’ was a hot title. It was heroic. Every kid knew about the Mercury astronauts and the Gemini astronauts; every kid knew about the Green Berets. And they saw it as a commercially viable concept that could at that moment in time work. And it didn’t.

“But if you look at the attitude of the times, you can see why they decided to go in that direction.”

Elliot Maggin (writer, 1970s Shazam series, Kingdom Come novelization):

“ …I never saw that. I’ve got to read this.”

And of course there were the underground comics — and even there, Captain Marvel made an impression. In his underground book Wonder Wart-Hog, cartoonist Gilbert Shelton teamed the title porcine up with a number of Golden Age parodies, including Captain Madball, who could turn into a super-hero by shouting the name of an ancient wizard — “Ralph!”

But there would soon be two characters with the actual name “Captain Marvel,” who would change the Big Red Cheese’s history forever.