The Heroes of Fawcett Comics

An Oral History of Captain Marvel (4/12)

The Lost Years, part 1

By Zack Smith • December 28, 2010

The Fawcett Years: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 The Lost Years: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 The Shazam! Years: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 • New Beginning Modern Years The Future

© Zack Smith; originally published by Newsarama

"The Lost Years" looks at the years when Captain Marvel wasn’t being published. Even though Captain Marvel wasn’t on comic shelves, his influence was felt, in comics, in creators, and in popular culture. He might have been gone, but he wasn’t forgotten.

Captain Marvel: After the Fall

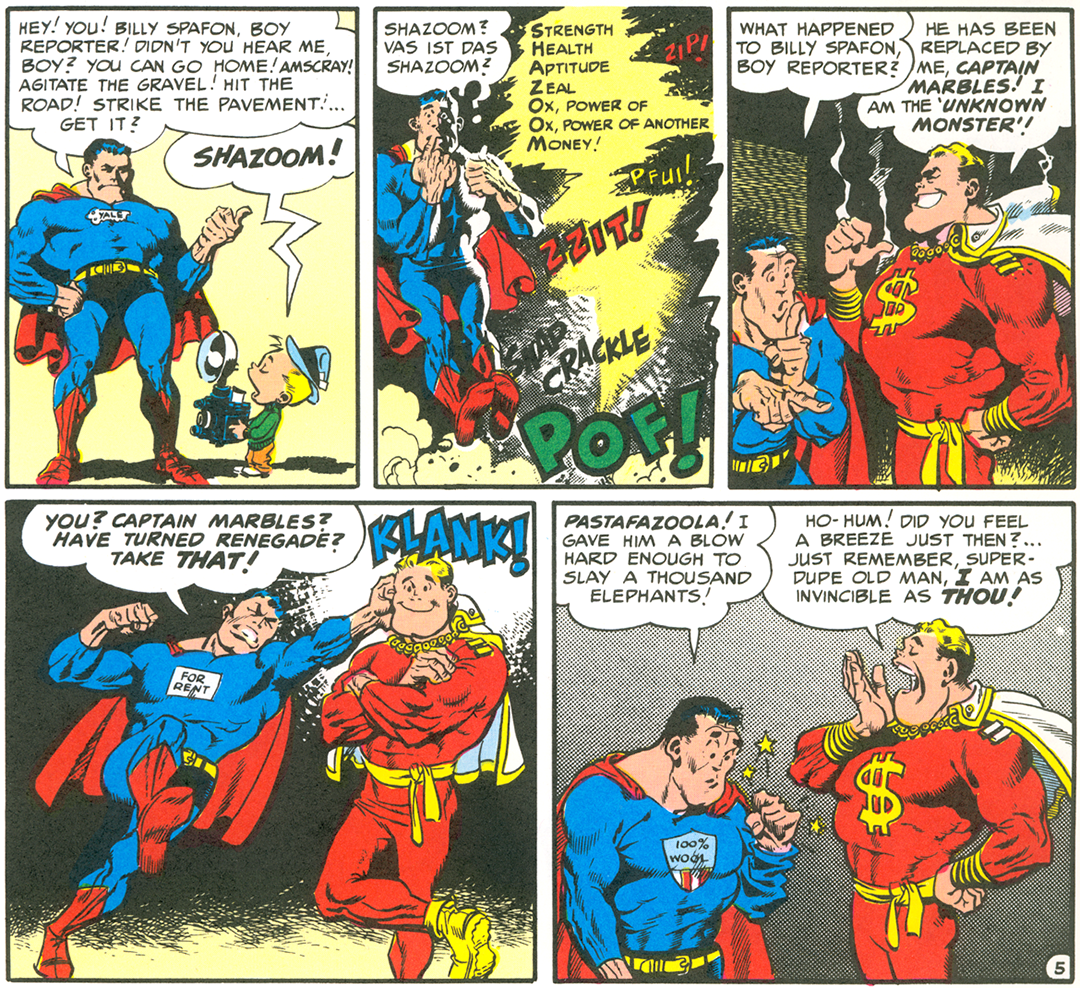

Superduperman & Captain Marbles

From 1954 to 1973, Captain Marvel and his friends were absent from the comic book racks of newsstands. But their presence was still felt, even as comics moved on.

Chip Kidd (author, Shazam!: The Golden Age of the World’s Mightiest Mortal):

“With this character, it’s remarkable that you have this gap of time between 1953 and 1972. I think it was a case of, “Out of sight, out of mind.” There wasn’t any Captain Marvel to think about except the old stuff, and it would have been much, much harder back then to read the stories.

“And if you didn’t have access to the back issues, how would you know of the character, except the name? Of course that led to Marvel Comics trademarking the name.”

Times were already changing in the comic book industry. Even before Captain Marvel disappeared from comic shelves, his longtime “rivalry” with Superman was mocked in the classic Harvey Kurtzman story “Superduperman” in an early issue of EC’s MAD with the title character battling “Captain Marbles.”

Comics were darker and more self-aware — books about horror, crime, war, Westerns, romance and funny animals all competed for shelf-space. Ironically, the line’s cancelation probably helped Captain Marvel and friends avoid the anti-comic scrutiny from the likes of Dr. Frederic Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent that helped lead to the formation of the Comics Code Authority — and killed most of the horror and crime books.

But even as trends moved away from super-heroes, Captain Marvel remained a fond memory for many fans. In a way, he was almost a “forbidden” character.

Elliot Maggin (writer, 1970s Shazam series, Kingdom Come novelization):

“When I was a kid, my parents owned a candy store, and they sold comics, and I remember Captain Marvel from back then. I was maybe two, three, four years old. I remembered him as a character; I didn’t remember specific stories, as I wasn’t old enough to read back then. But I learned to read through comics, and it might have been a Captain Marvel comic that made reading special to me.”

Michael Uslan (Executive Producer of all Batman movies):

“It was like the greatest super-hero that could ever have been created, because there was something mystical about it. There was something phantasmagorical about the idea, because it was so hard to find those issues.

“And when you did find them, it was another shock, because it was so starkly different in tone and in art from anything we were exposed to in the 1960s and early 1970s of the world of super-heroes. And you just wanted to find out more and more and more about it.

“I wanted to know more about the super-heroes who worked with Captain Marvel — like this “Marvel Family” and how Mary Marvel compared to Supergirl or Captain Marvel Jr. compared to Superboy. And the idea of a boy who could turn into an adult super-hero with a magic word was just fascinating as a kid. Talk about wish fulfillment.

“It was this grand, elusive mystery, and we tried to find out everything we would about it. And that’s how legends are born and grown.”

In some ways, Captain Marvel helped promote the idea of comic book fandom — comic fans helped keep Captain Marvel’s memory alive by trading issues back and forth, or writing about the characters for the original “fanzines.” Of course, this led to trouble on occasion, such as when Roy Thomas wrote a story about Captain Marvel with reprinted artwork for his fanzine Alter Ego.

Roy Thomas (writer, Shazam: The New Beginning, others):

“What happened was I got a letter from an editor at Fawcett named Ralph Daigh. He had become aware of the piece somehow, and was sending me — I don’t know if it was officially a cease and desist order, but it amounted to that.

“It wasn’t a legal document, it was a letter saying the piece could not be published with any artwork of the Marvel Family in the future because of the terms of the settlement with DC. It didn’t go into details, but obviously it was unsettling.

“The same thing happened with Jules Feiffer when he did The Great Comic Book Heroes — he was only allowed to reprint one page of Captain Marvel. Years later, I was allowed to reprint what I wanted, though.”

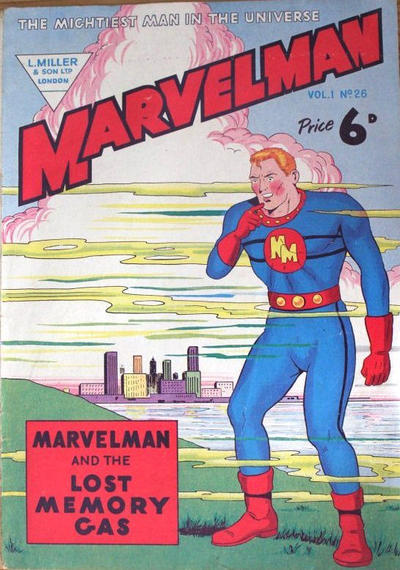

Marvelman

Demand for Captain Marvel remained strong. In the U.K., publisher Len Miller sought to continue his success with Fawcett reprints by creating a British version of Captain Marvel. Writer-Artist Mick Anglo created “Marvelman,” a reporter named Mickey Moran who could become the blue-clad hero by uttering “Kimota!” (“Atomik” backwards). There was even a “Dr. Gargunza” to substitute for Sivana.

With many characters mirroring Captain Marvel — including “Young Marvelman” and “Kid Marvelman” for sidekicks — Marvelman carried Captain Marvel’s torch until 1963. But a darker, more realistic revival a few decades later would bring the character a new level of critical acclaim…and launch a few lawsuits himself. Let’s not skip too far ahead, though.

The Fly

Once in a while, a new character would pop up who mirrored Captain Marvel. Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, who had worked on some of the early Captain Marvel tales, created a considerably weirder version with the Fly, an orphan who could turn into an adult fly-man thanks to…extra-dimensional “Fly People.”

Elliot Maggin:

“Years after the book was canceled, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby did a book called The Fly. I remember reading it as a kid, I was maybe eight or nine years old, and I was hooked. It was about this super-hero who changed into a little kid — an adult super-hero who was a kid in his secret identity. And as an adult, he was the same person as the little kid! To hell with the sensibility! I thought that was great!

“And then, after the third or fourth issue, he was a grownup. I kept reading to see someone comment about this in the letters column, and they replied, ‘Well, didn’t you think it was a little silly to have a kid, turn into a grownup?’ I said to myself, ‘No, I didn’t think it was silly at all,” and I stopped buying the book.’”

The Legacy of Otto Binder

Fawcett continued publishing magazines outside of comics, and Captain Marvel’s creators moved on as well. C.C. Beck, Captain Marvel’s co-creator and most prolific artist, moved into commercial work, but other creators stayed in comics, most notably Otto Binder.

After Fawcett stopped publishing comics, Binder continued a successful comic-writing career, and even saw one of his SF stories adapted into the "I, Robot" episode of the original Outer Limits with a young Leonard Nimoy.

Ironically, Binder’s greatest success in comics was for Captain Marvel’s biggest “rival,” Superman. Under editor Mort Weisinger, Binder created or co-created such characters as Supergirl, Brainiac, the Phantom Zone, the Fortress of Solitude, Krypto the Super-Dog and the Legion of Super-Heroes. These imaginative characters reflected many of the ideas he'd done in the "Marvel Family."

Mark Waid (Kingdom Come, other Captain Marvel stories):

“If you look at it, Binder had written the great majority of the Marvel Family stories — something like half of the Captain Marvel, Mary Marvel, Captain Marvel Jr. stories ever.

“Once the books went over, he started doing odd jobs in comics, and he moved to DC and did the first 30 or so issues of Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen and other Mort Weisinger work. But after a few years of that, his work coincided with Weisinger’s 1957–1958 expansion of the Superman family and universe.

“If you look at that era, Binder was at the front and center of it. He gave us Supergirl, he gave us the Fortress of Solitude, he gave us all that stuff, under Weisinger’s watch. It’s clearly him taking that sense of world-building at the heart of the Marvel Family and taking it to Superman, and the Superman universe was much richer with him, no question.”

Elliot Maggin:

“Every once in a while they’d give Jimmy superpowers to fill that Captain Marvel Jr. niche. Mort (Weisinger) used to say every six months he’d throw in some new element to shake up the continuity, whether it was a fifth-dimensional imp or Supergirl, or some new kind of Kryptonite. And who knows where he got those ideas?

“Whether he co-opted them, there are fundamental ideas that you can re-interpret in a fundamental context. When I was writing context, people asked me where I got my ideas, and I’d say, ‘There are only eight plots.’

“One day, it occurred to me to write them down, and I could only come up with one: Decision, conflict and resolution. I find it difficult to say whether someone got his idea one place or another. You can’t even copyright an idea, (though) apparently you can trademark the name ‘Captain Marvel.’”

Jerry Ordway (writer/artist, The Power of Shazam, others):

“You really saw a Superman Family like the Marvel Family, even with things like the Legion of Super-Pets. It was a nice antidote to the horror comics of the time.”

Michael Uslan:

“It was still Otto Binder, and Otto was a genius at creating stories the way he did, especially stories for kids, and especially stories that created awe and wonder in kids. And I think his science fiction background played into that.

“You add in Mort Weisinger as editor, and what you have is the basics of the Marvel Family being developed in a way that gave Superman a Superman Family, something he did not have in the 1940s and early 1950s.

“The creations Otto brought to Superman really defined that version of the Silver Age from the version of the Golden Age. His handling of Lois Lane, his handling of Jimmy Olsen, the Legion of Super-Pets is a great example. The feeling of family between Superman and Kara. The emotion he brought to his stories. There’s no way you can count them out.

“This is a man who, as a writer, brought Captain Marvel to the top. He really, truthfully did, and he did the same with Superman, with that same light tone.”

Being a comic book creator back then wasn’t a job most people admitted to doing, but Binder was one of the first pros to directly interact with fans.

Roy Thomas:

“Otto was great. He was one of the original people I was in contact with from the time I took over Alter Ego in 1964. He sent me all this material — photographs, and scripts for newspaper strips he was trying out, and permission to try them out. When he came to St. Louis for business in 1965, we had lunch, and he was the first professional I ever met.”

Michael Uslan would grow up to become an immensely successful producer in Hollywood, one who would help create the modern super-hero film as we know it with Tim Burton’s Batman all the way through The Dark Knight. In the early 1960s, though, he was just a young fan who became friends with one of his writing heroes.

Michael Uslan:

“My friend Bobby Klein and I were 10 years old in Ohio, and we were part of that first wave of comic book fandom just as it was getting up and running. We read in Alter Ego that Otto Binder lived in New Jersey, which is where we’re from. And when you live in New Jersey, you realize you’re never too far away from anyone else who lives in New Jersey.

“So we tracked Otto down and we wrote him a letter saying we were fans and wanted to interview him for a fanzine we were putting together on the Fawcett story. And he was very welcoming, and invited us up to his home in Inglewood, New Jersey — we convinced my mom and dad to take us up there on a Sunday.

“That turned into about a 10-hour session with Otto at his home. And we became friendly from that moment on.

“Otto opened up the world of the Golden Age to 7th-grade comic book-fanatic fanboys in 1963–1964. It was amazing. We learned all about the Golden Age; we learned about all the super-heroes we were unfamiliar with, having failed to grow up in WWII. We learned how comic books were put together, how the companies began, all the writers and the artists and the editors and the colorists involved in the process, and a lot of people who were our idols at that time.

“We had a list of about 260 questions to ask him. He took us through the entire Fawcett story. When we were done with that and getting ready to leave, he piled us up with copies of every comic he had an extra copy of, whether it was Captain Marvel Jr. #1 or the first Captain Marvel story he’d ever written back in the earlier days of Whiz Comics and various autographed books and scripts he’d done, and whatever else we could carry.

“But perhaps the most important thing he’d done was because of our interest and our thirst for knowledge, and because as kids we’d impressed him, he put me in direct touch with C.C. Beck and Fawcett editors like Will Lieberson and Wendell Crowley, and a number of the people who used to work at Fawcett.

“As a result of this, I began these ongoing letter-writing dialogues with these people, the longest of which was with Beck. And it was fascinating. These were of course the days way before the Internet, and the only effective way you had to communicate was through letter writing. That opened my eyes and filled in so many blanks. Bobby and I became serious Captain Marvel fans, and I was a big Fawcett collector.

“The next time I interacted with Otto Binder in a significant way was the first comic convention ever held anywhere. This was in 1964, in a fleabag hotel in downtown New York called the Broadway Central. And Otto was the guest of honor.

“He was one of the very few pros who showed up there. Most of the pros in the business were afraid to show up at that first comic con — there were maybe 200 of us there, and they couldn’t believe that there were adults who were still comic book fans who weren’t mentally impaired or some sort of sociopaths.

“I think at that first convention, outside of Otto, Gardner Fox was there, Bill Finger…from Marvel, Stan Lee was afraid to show up, so he sent Flo Steinberg, his secretary [laughs]! It was there were everything you know about comic book conventions — costume contests, panels, auctions — was invented.

“Otto took Bobby and me by the hand, and he showed us for the first time what original artwork looked like, and how you go from pencils to inks, and then he said, ‘How’d you boys like to meet the creator of Batman?’ And that was how we met Bill Finger.

“Otto was a mentor to us, and he was the one who opened up the world of Captain Marvel to me.”